I was really pleased when Ros McMullen asked whether I could attend a @HeadsRoundtable Meeting following a New Year blog post “Ofsted Get it Right for Once … Oh No They Didn’t”. This is a summary of a short presentation prepared for the meeting at Huntington School in York, hosted by John Tomsett.

John Tomsett leading a very progressive teaching approach with yellow stickies. Questions for MG & SMW next Monday

The presentation was one of a number delivered TeachMeet style to get the discussions on Ofsted going.

The title is deliberately provocative and obviously plays well to a teaching profession that is seeing the caustic effects of an inspection regime that has lost its way on a number of key issues. Ofsted’s ability to remain independent is being worryingly challenged, through appointments, and what you sense is politically driven ideological changes rather than well evidenced, carefully thought through practice. Much of the good it potentially could do is being lost through an aggressive and adversarial culture.

The title is deliberately provocative and obviously plays well to a teaching profession that is seeing the caustic effects of an inspection regime that has lost its way on a number of key issues. Ofsted’s ability to remain independent is being worryingly challenged, through appointments, and what you sense is politically driven ideological changes rather than well evidenced, carefully thought through practice. Much of the good it potentially could do is being lost through an aggressive and adversarial culture.

However, cards on the table, we are not ready to see the total demise of Ofsted, not yet. It is not unreasonable for us, as a profession, to be held accountable for the very large sums of public money spent each year. The lack of accountability from within the profession itself, in previous decades, did not serve our young people well. As a profession I think we should be calling for a “Revise, Revise then Demise” strategy to Ofsted reform. Politically it is highly unlikely that radical proposals to simply remove Ofsted tomorrow would even be seriously considered.

Revising Ofsted – Part 1a

It’s easy to get carried away with what we might like to see but early stages need to focus on practical steps which could be implemented fairly easily and soon.

There are some simple steps, already in the public domain, which could be acted on fairly quickly. Brian Lightman, ASCL’s General Secretary, has long argued for a higher quality and greater consistency within Ofsted inspection teams and the presence of serving headteachers. With a network of National Leaders of Education and other serving headteachers who might agree to serve on inspection teams this would seem eminently possible. In addition, the previous “risk assessment” of schools that seems to have fallen into abeyance should be reinstated.

In December 2012, ASCL issued a position statement; inspection should

‘… involve a professional dialogue between leaders and appropriately qualified inspectors, rather than being something ‘done to’ schools and colleges by Ofsted.’

The table above is taken from Summer Term 2013 Ofsted Inspection data presented at ASCL’s Regional Conferences. It is a summary of secondary school report grades covering one in seven secondary schools. Ofsted were busy that term it seems and since. The conflation of the Overall, Achievement and Quality of Teaching grades is clear for all to see. In December 2013, Ofsted revised their subsidiary guidance to inspectors stating “reports will be given additional scrutiny” where the grade for Behaviour & Safety is higher than Overall Effectiveness. Will future reports end up with five identical grades all being driven by Achievement?

Suggestions for how we might revise the Ofsted Inspection process in the short term might look something like this:

I remain totally unconvinced that Ofsted can actually make any rigorous, balanced and valid determination about the quality of teaching or behaviour over time that would hold up to the slightest amount of scrutiny or meet research based standards. There is a sense that the Achievement grade drives everything. The leadership and management grade seems to play “follow my leader” and is far too subjective to be reported on sensibly. Ofsted should accept the limitations of its approach and move to a single grade for Overall Effectiveness. Issues relating to quality of teaching, behaviour and leadership & management are governance issues, Ofsted should focus on outcomes and current data.

It must feel wonderful for Ofsted to grade your school as outstanding and there is something aspirational in maintaining this as a grade. However, the ability of an Ofsted team to discern this is questionable and the cliff edge nature of each grade boundary, with schools sitting just one side or the other of it, is unhelpful. Every school a good school is the mantra and so it should be our goal. A school is either effective (or possibly termed Good or Better) and we need then to focus on supporting and challenging schools that are not yet good.

Moving to More Radical Revision

The Updated #Progress8 May Just Be A #Gamechanger. The new Progress 8 measure, setting aside the confusion over the interchangeable nature English Language and English Literature, has the potential to be very powerful. Within the document it discusses the setting of a benchmark for expected performance, once current churn in the system from the new examinations and accountability measures has calmed down, three years in advance of students sitting their GCSE examinations. Put rather crudely, the Department for Education would use the results of the 2015 cohort to set in advance what would be Expected Progress, in terms of the Attainment and Progress 8 measure, for students sitting their exams in 2018.

This produces the possibility for improvements in the quality of education, offered by schools, to be recognised through as many schools as possible attaining and achieving the fixed benchmark or better. If this benchmark was fixed for ten years or so (I’ve plucked this number slightly from the air) then what we have is a standard to strive to get every school over ensuring that all children are at a good or better school. The system then resets and a new benchmark is determined and as a system we rise to the challenge of this higher bar.

The second stage of revising Ofsted has to be radical in so much as it stops inspecting individual schools, hence school visits stop, and moves to inspecting the system. No more individual reports on schools. The short term reputational damage to schools labelled as “Requires Improvement” or “Inadequate” can lead to difficulties in recruiting staff and loss of confidence from prospective parents who then choose other schools for their children is unhelpful. It is particularly unhelpful for the children currently being educated in the school, the name and shame culture has never effectively added anything to the inspection system.

Photo Credit: http://www.smartdraw.com

These are probably the suggestions that require most thought, there is a hidden danger here waiting to trap the unwary. ASCL has been very clear that moving to a table top exercise has the potentially massive danger of limiting the only valued outcome from a child’s education to their examination results as opposed to this being one of a number of important outcomes from a child’s time in compulsory education.

OFSTED SAS

The removal of individual school inspections mustn’t be a money saving exercise as these funds can be diverted to a revised Ofsted School Achievement Service – Ofsted SAS – whose responsibility it is to support those schools that are not considered to be delivering an effective education, in a genuine partnership, as a replacement to their current regional “monitoring & scrutiny” style approach. Ofsted SAS will also have access to high performing schools and can produce reports, in a similar manner to those currently produced, about highly effective practice within the system. They become part of a knowledge sharing network.

Ofsted reports should focus on whether the system is improving, over time, using the Attainment 8 and Progress 8 measures against a fixed benchmark. There is also the potential then for more local scrutiny around school clusters, families, chains of academies, federations of schools and groups of local authority schools. Clearly this assumes that these structures replace the current middle tier within education, in a coherent manner, and every school belongs, contributes and learns within a structure that is bigger than itself.

Longer Term Goals

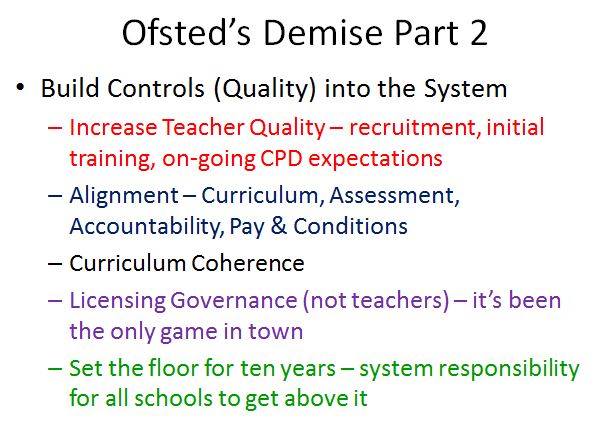

The actual demise of Ofsted may be a decade or more away as we need time to build more quality in our system through judicious adoption of some of the strategies from High Performing School Systems internationally to transform further our own education system. To misquote Professor Tim Oates a bit, “we’re not in crises but we are stuck”. The next stage of education reform must be informed by and through schools.

One to focus on here in the medium term is potentially Licensing Governance rather than licensing teachers. Changing governance has been the one consistent theme over the past fifteen to twenty years that successive governments have used to instigate improvement in the system.

The possibility of licensing governance through contractual arrangements for a new middle tier is one of a number of ideas I’ll return to in a future blog. To be clear, if we want the Demise of Ofsted we still have some way to go in taking responsibility for the system and locking quality in.

With thanks to Ros for the invitation to the event, John for hosting and colleagues for their thoughts, challenges and company. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the day with @HeadsRoundtable.

Some additional thoughts from speakers and round the table discussions:

- Can we improve the quality of inspection teams by having fewer inspectors? The quality of some training and some inspectors (though not all) were felt to be lamentable.

- How will the tension between a self-improving school system and externally led centralised inspections be balanced? Should external inspection be focussed on schools’ ability to self-evaluate?

- Can the process of peer led review assist in building quality into the system?

- In cross phase clusters/federations/chains of schools should the progress from 3-19 be the key accountability metric?

These suggestions are both coherent and convincingly realistic to my mind. With regard to the danger of a table-top exercise focusing exclusively on exam results, there could be other measures that give a broader picture. What they would be is a very open question but destination data, attitudinal surveys, pupil interviews, maybe. In each case the hazards are probably obvious but there are some robust methodologies that could be taken from educational research that might be useful although the latter two would require school visits. I also think the contextual value-added question unavoidably rears its head in any scenario where Ofsted judgements are completely data-driven unless a school is compared to other, similar schools; it’s always hard to be matched up against national benchmarks with a cohort that is skewed right to either end of the national data set and I’ve yet to encounter an inspection team well-enough versed in statistics to convince me that they had a genuinely solid understanding of statistical (in)significance and the limitations of school data although that ought to be fixable. The only other part of your vision which generated questions rather than humble respect, is the move to three grades (which I appreciate you question yourself). There are some things which go with a Grade 1 that require some thought. At the moment the Grade 1 opens the door to Teaching Schools, SCITTs etc. I worry about this given the number of downgrades which might be expected over the next couple of Ofsted cycles and the impact of these on Teaching Alliances etc. A move to a three grade system solves that problem but also significantly lowers the bar to accessing these options and might lead to a bit of a chaotic free-for-all. How would a ‘Good or Better’ school be judged worthy of Teaching School status? Maybe that’s not so hard to answer but it is an issue if the ‘obvious’ benchmark on achievement is removed.

Posted by dodiscimus | February 4, 2014, 8:50 pmThanks for your comment. I’m not sure about the three grades myself but remain totally unconvinced that Ofsted are able to make such fine differentiation with any validity. I know members of HeadsRoundtable will read this post and pick up your comments.

Posted by ExecutiveHT | February 4, 2014, 8:54 pmReblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Posted by teachingbattleground | February 5, 2014, 6:34 am